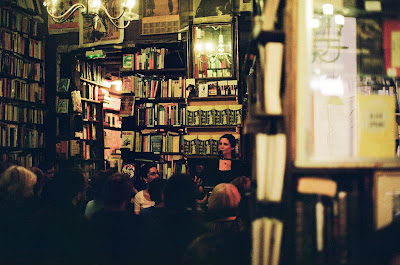

In honor of the publication of her edition of Sylvia Beach’s letters, I wanted to do something special here at Fernham. As part of Sylvia Beach Week, Keri Walsh and I “interviewed” each other over email. We continued the conversation we began at her reading at Bluestockings books in May, touching on the challenges of editing, on women modernists, on bookstores, archives, and common readers. We could barely stop talking, so the conversation is in four parts. I hope that you enjoy reading it as much as we did writing it!

Anne: Anyone who loves Sylvia Beach must also love bookstores. Can you tell me about one or two of your favorites and what they offer?

Keri: Some bookstores have such intellectual energy that they make you feel smarter.

Blackwell’s in Oxford is one of them.

You can take your notebook in there and emerge three hours later having done all the research for your latest piece of writing. Blackwell’s has every book you could ever want, at least in the Humanities, and you never know who’ll be sitting beside you in the second-floor café.

There’s a certain jetset element, a

Hello magazine blend of Rhodes Scholars and children of foreign potentates.

It makes for glamorous people-watching: you can try to pick out the next Bill Clinton. The main Blackwell’s shop, which opened in 1879, is located in an old house right across the street from the Bodleian, and from the café you can see across the street to the dreaming spires and the Sheldonian theatre.

I think I grew to love Blackwell’s because it gave me what the Bodleian couldn’t. Some days I didn’t have the patience for Old Boddy: the books are locked away, can only be called up in small quantities, and you can’t wander in the stacks or take things home, and you certainly can’t drink Diet Coke in there. All of this leads me back across the street to Blackwell’s. There’s a huge floor in the basement called the Norrington Room (a friend of mine used to call this area the TARDIS, after Dr. Who’s police box). The store had to excavate beneath Trinity College’s gardens to accommodate it. The TARDIS holds the philosophy, religion, feminism, film, and cultural studies books. That’s where I would disappear to read things that weren’t quite approved of by my tutors— French feminism, American cultural studies, and anything else that seemed too jargony or flighty. And then, if you hike up about five flights of stairs, you get to the second-hand section. That’s a great place to find out-of-print women’s novels published by Virago in those gorgeous green-backed books—books like Rosamund Lehman’s Dusty Answer, my favorite best-seller of 1927.

Meanwhile, in London: last summer I discovered Samuel French’s Theatre Bookstore. It caters to an entirely different clientele: the city’s actors. It’s tucked away on a very quiet corner of Fitzrovia, and the walls are full of notices of auditions and ads for plays. They carry every thespian thing you could ever want, and then some things you didn’t even know existed. In that second category, I picked up a script for Mindy Kaling’s spoof of Good Will Hunting called “Matt and Ben.”

Keri: Please tell me about your favorite bookstores, and what they offer.

Anne: I grew up going to

Seattle’s University Bookstore with my family on the weekends. The children’s section and the magazines were on a balcony overlooking the main floor. My father would browse history while my mom, sister, and I picked out books for ourselves. I remember presenting him with a stack of two or three and having him assess my choices, and substitute one book for two others he deemed better. Those were golden hours.

The summer before graduate school, when I was 21, I worked at Bek’s Books in Seattle. It was an ordinary independent bookstore in an underground mall in a bank building: precisely the kind of bookstore I had scorned before the owner, a family friend, offered me a much-needed job. It had New York Times bestsellers near the door, travel books, a romance section, cookbooks, and a small children’s section. It was a place for bank tellers and lawyers to pass through on their lunch break. My snobbery faded pretty quickly. I loved the other clerks there and I grew to love the passionate reading tastes of people who then looked to me very ordinary, very middle-aged. I was working my way through the “recommended reading” from Yale that summer and driving everyone—myself included—crazy by answering customer’s queries about what I was reading with “Oh, The Aeneid.”

Now, I dream daily of Greenwich Village’s

Three Lives Books. I feel smarter just going in. That’s a reader’s store: a store to discover great fiction. The staff is wonderful and friendly and though I don’t go nearly as often as I like, they are kind and so knowledgeable and genuinely interested in reading. It’s a lovely little space: just big enough to linger in, but small enough not to be overwhelming. The perfect stop on the way to the PATH train & back home to Jersey. And, of course, in London, I have to go to

Hatchard’s, the shop Clarissa browses and still a great browsing store in an old townhouse off Piccadilly (though it’s a chain now).

I wish New York had a good academic bookstore: I miss having a place to browse through the books that I see advertised in The New York Review of Books (on those rare occasions when I get to it). Bluestockings comes close, but I want a broader political range, not only radical books. My husband tells me that NYU has just redone its bookstore and made it into a flagship. I have high hopes for that. I haven’t spent a lot of time in Oxford, but I know just what you mean about the Blackwell’s there: it’s certainly a pilgrimage spot for me. Seminary Books in Chicago is the only American bookstore I know that comes close to giving you that incredible feeling of stretching your brain, making you long to read serious, important books, new and old.

New York’s

Drama Bookshop is a space like the one you describe in London. Do you know it? Kris Lundberg of the very Woolfian Shakespeare’s Sister Theater Company did a staged reading there on Woolf’s birthday one year and invited me to speak. They have a small black box performance space in the basement. If you haven’t been, treat yourself!

Keri: When describing Sylvia Beach’s taste in books and her reading practices, I often end up borrowing Virginia Woolf’s idea of the “common reader.” Making books available to a wide range of people in every walk of life was important to both Woolf and Beach. And they both liked to make fun of academics who took themselves too seriously (I love Woolf’s academic satires in To the Lighthouse). Can you say something about Woolf’s fondness for “common reading,” why the concept is so important to her, and also perhaps what role it plays in your own editorial practices, teaching, or reading?

Anne: The notion of the common reader is really important to me. Woolf writes about reading what one likes and never pretending otherwise. She wasn’t always so confident, but by the time she was in her forties—my age now—she was. Her confidence, her refusal to let others turn her away from Euripides or a Countess’ memoirs, gives me confidence when I feel others challenging my choices.

One of the things I love about blogging is the happy randomness of it, the way it allows you to graze around the web until, suddenly, you hit an unexpected pocket of intensity—some blogging community where everyone is writing fan fiction about Harry Potter or interacting with their favorite romance novelist or enjoining a group of friends to work their way through

Don Quixote as I did with Bud Parr a few years back. My friend Lizzie Skurnick (who blogs over at the

Old Hag and wrote

Shelf Discovery) is my 21

st century model for common reading: she can rattle off the plots of great forgotten bestsellers from the 70s and then, in the same paragraph, she’ll tell you about what she’s getting from this rereading of Thackeray.

Although I never read as much as I want to read, reading is the great pleasure in my life and I love peopling my life and my imagination with—well, just everything I can gobble.

When I teach, though, I want to communicate enthusiasm, but I don’t teach a lot of pop. The fun of pop and light fare is discovering it for oneself. I am happy to refer to Lady Gaga in the classroom, but I don’t teach her or Nora Roberts or Eat, Pray Love. My sense is that you want a teacher for those texts that are so intimidating or difficult that you wouldn’t tackle them on your own.