It would have been 1981 or 1982. I was in high school and babysitting on a weekend night for my cool yuppie neighbors. The parents came back all excited from their screening of “Claire’s Knee,” eager to tell me that I reminded them of Claire.

To this day, Puritan that I am, I cannot quite imagine myself into the position of a young girl who excites a middle-aged man’s lust. I was a bit freaked out by the comparison at the time. Did that mean that Mr. X…? But Mrs. X was giggling, too? It seemed too gross, too complicated to take in, so I avoided that film for years.

But, still, they were very cool. And I filed Eric Rohmer away as a director to watch. When I did, I fell in love.

More than any other film director, Rohmer is mine: I love his films and I love his women. I don’t know the Six Moral Tales as well as later films, so I was surprised to read in the Times obituary that his characteristic subject is “a man who is married or committed to a woman finds himself tempted to stray but is ultimately able to resist.” In that telling, he sounds like such a male director, but to me, his films have always seemed really friendly to women.

But then, the truth is, I identify with his heroines: nervous women, liable to talk to much, women who wear no make-up, and whose beauty varies tremendously from shot to shot—just as one’s own beauty does. Rohmer always lets you see that his actresses are beautiful. He lets them know it, too. But he also shows them doubting it in moments of stress or shows their beauty and confidence failing them just when they want it. Beauty is not everything, of course, but this is film—French film—and it’s so visual. And, for Rohmer, that raw, imperfect, eccentric beauty serves as a visual metaphor for worthiness—both to oneself and to others. It does not hurt that the women he directed are clearly very very smart: their beauty emanates from their intelligence.

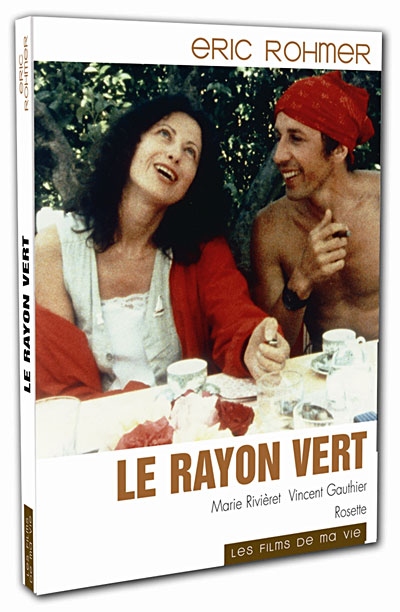

My favorite is “Le Rayon Vert” or “Summer.” It perfectly captures so many of my own vacationing dilemmas in my twenties and thirties. A young woman, newly single, must quickly make plans for a vacation during the national August holiday. She waffles from neediness—she’ll just go to the Alps and pop in on her ex—to friendliness—she’ll just be an easygoing add-on in a big family house—to bravery—she’ll go off to the shore alone. Alone on the shore, her bravery is intermittent. She is rude to cute men and kind to the wrong people. Her loneliness betrays her until she figures out how to be alone. It’s such a painful, uneven, crazily raw performance. It does so many things that an American mainstream chick flick just cannot approach: it allows you to see a young woman’s loneliness, including some of the humiliations of that loneliness, without humiliating her. It shows that loneliness as a mood--her boyfriend just dumped her, after all—not a condition. I cannot get enough of it.

Last spring, Lauren hosted Jonathan Baumbach introducing “An Autumn Tale,” a late Rohmer film that shares a lot with “Summer.” I could take or leave the pretentious introduction, but the film itself was a glorious masterpiece: beautiful and interesting narrative, full of rich talk. It—and Rohmer himself—strikes for me, the perfect balance of intellectual filmmaking: still enough of a movie to be fun on a date, but provocative enough to inspire an essay.

Eric Rohmer died earlier this month at the age of 89. Marina Bradbury’s charming tribute includes this memory of her one visit to him a few years back:

"Excusez-moi," he said politely, and ducked into the next room, shuffling back moments later with a pile of coloured exercise books. He explained excitedly that the colour of each matched the palette of each particular film. For example, yellow in La Boulangère de Monceau (1962) reflects the colour of bread, whilst blue in Pauline à la Plage (1983) represents the sea.

And you can read A. O. Scott’s appraisal of his career here. What a wonderful legacy he has left behind.