Anne: For people who don’t know her, tell me a little about Sylvia Beach. And for all of us, what draws you to her story?

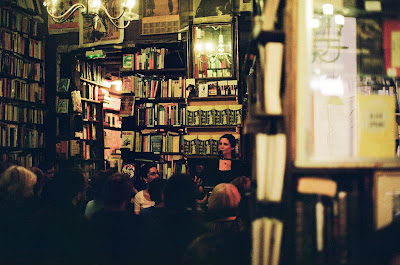

Keri: In introducing Sylvia Beach, I’ll start by naming the two achievements that made her proudest: “publishing Ulysses, and steering a little bookshop for 22 years between the wars.” Her bookshop was Shakespeare and Company, and it would become legendary as the spiritual homeroom of expatriate Paris. Writers like Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, H.D., and James Joyce wiled away the hours there and Beach provided them with books, a mailing address, places to live, introductions, French tutors, advice on publishing, and anything else they might need in Paris. With the help of the French printer Darantière and a committed bunch of typists, she brought out Ulysses in 1922 when it was banned in England and America.

Beach was born in 1887 and she grew up in Princeton, New Jersey where her father was minister at the local Presbyterian church. She was taken to France as a child and she adored it. She returned during the First World War and spent time doing agricultural work near Tours, and then working for the American Red Cross forces in Belgrade. When she returned to Paris at the war’s end, she fell in love with Adrienne Monnier, the owner of a French-language bookstore called La Maison des Amies des Livres. It would become an inspiration for Sylvia’s own shop. With Monnier’s help and a gift of $3000 from her mother, she opened Shakespeare and Company in 1919. Little did she know that American writers would soon start flocking to Paris to take advantage of the exchange rate and the reprieve from Prohibition at home. She was the right person in the right place at the right time, and for any American writer abroad, her bookstore felt like home. Beach is described affectionately in so many memoirs—most famously, in Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast. Hemingway was moved by the trust she showed him on his first visit: he couldn’t pay the lending library fee, but Beach let him walk off with a bunch of books and a promise that he’d come back to pay the bill someday. In a time before English books were readily available in Paris, he and his wife Hadley were so excited by the prospect of all the reading they could do thanks to Shakespeare and Company. Hemingway describes coming home to Hadley with the good news, telling her, “we’re going to have all the books in the world to read and when we go on trips we can take them.” Hadley was delighted and amazed by Beach’s unusual business practices:

“Would that be honest?”

“Sure.”

“Does she have Henry James too?”

“Sure.”

“My,” she said, “We’re lucky that you found the place.” (38)

Anne: How did you come to discover her letters? And how did you come to see that they could be a book?

Keri: Maria DiBattista, one of my professors at Princeton, was the first to show me what a rich deposit of Sylvia Beach’s letters and belongings we were lucky to have at Firestone library. While I was reading Ulysses in Maria’s class, she asked me to come with her to give a presentation on Sylvia Beach to a group called The Friends of the Princeton University Library. She asked me to pick out one of Beach’s letters to present to the group, and I chose one that is still among my favorites— a letter that Beach wrote to Adrienne Monnier in 1940. It was written in French, and it provided a lovely sketch of her relationship with her customers in the bookshop, and then a list of some of her latest recommendations.

Then, again through Maria’s mentorship, I helped to curate an exhibition at the Princeton University Library. It was called “Portraits of the Lost Generation,” and it featured Man Ray’s photographs and other Surrealist materials mostly drawn from the Sylvia Beach Papers.

I loved all the time I spent in Sylvia Beach’s company. Her letters were significant for modernist literary history, to be sure, but they were also so charming in their own right. And they told the story one American woman’s life in Europe in the first half of the twentieth century. In all my reading about women’s role in the First World War, I had never read such a detailed first-person account of what it was like to work in Serbia with the Red Cross. And it was even more fascinating to learn that though she was expected to get married and live a conventional life, Beach was wearing pants and swooning over women. With a sense of humor and a kind heart and a romantic spirit, she had managed to carve out a life that worked for her in Paris, to live in accordance with her own desires while also serving others.

I couldn’t help but marvel over the fact that her letters had never been published. Many scholars had looked through the collection while writing biographies of Hemingway, Joyce, Fitzgerald, Stein, H.D., but the only person who had made thorough use of the archive with an interest in Sylvia Beach herself was Noel Riley Fitch, Beach’s biographer (Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation, Norton). It was really my enjoyment of Beach’s letters that made me think they would be a good book. I thought that others might like to spend time with her too.

Anne: I have an obsession with the particularities of working in archives: it’s, for me, tedious work, always punctuated by elation and discovery. I love and hate all the rules and the various ways in which each archive has a distinct personality. Do you have any favorite anecdotes from your work in the Beach archive?

Keri: Archivists and researchers have curious, often endearing relationships. Ideally, they both love the archive and feel protective towards it. Your question calls to mind two very different archival experiences I’ve had, one with a well-known resource, another with a found treasure.

For my Sylvia Beach project I was lucky to work with amazing research librarians at Princeton. They knew the archive better than anyone, certainly better than I did. I depended on them daily, and learned how to accommodate myself to the rhythms of the archive. You can’t just barge in ten minutes before the library closes and ask for a bunch of manuscripts. You need to build goodwill. There’s a Jane Goodall effect: if you are simply physically present in an archive long enough, and follow its regulations, you end up becoming a familiar and trusted presence. That’s when you get to go backstage and bend the rules a bit. This process works best when you get to inhabit a particular archive over a long period of time. I was fortunately able to work on Sylvia Beach’s letters during my time as a graduate student at Princeton, meaning I had daily access to her papers over the course of four years. I spent many summer days hanging out in the Rare Books and Special Collections room, often bringing along research assistants or friends I had roped into helping me.

Since the Sylvia Beach project, I’ve been working mainly in theatre archives, and that’s even more exciting because they are so much less well-trodden than literary archives: there’s more potential for making big discoveries: you don’t have to satisfy yourself with finding an overlooked comma – it’s more like an overlooked box of letters. At the New York Public Library’s Billy Rose Theatre Collection, I was able to look at programs, scripts, photographs, and notes from a 1946 Broadway production of Antigone that wasn’t even catalogued by the library or listed in the Finding Aid. No one had seen this material since 1946, and bibliographically speaking, it didn’t exist. To get access to those papers took a lot of coaxing, some cajoling, and some begging. But the high of making contact with that archive, and discovering the missing pieces of a story I was trying to tell, were well worth it.

1 comment:

Very good stuff. Thank you!

Post a Comment